In Memoriam: RMS Titanic

The Parsons Turbine

Sir Charles Parsons, born in 1854 and raised in Birr Castle, Parsonstown, Ireland, had a fascination with mechanics throughout his life. As a young father, he designed a steam-powered tricycle for his daughter, as well as miniature steam locomotives. He also experimented with torpedoes and rockets.

To Parsons, the best part of an ocean liner was the engine room. On one Atlantic crossing, a story has him making his way to the engine room in his evening dress. He was found by the Chief Engineer crouched in the propeller shaft, listening to the music of the ship. When confronted by the Chief Engineer, Parsons engaged him in a conversation covering torsional oscillations and harmonic vibrations in the same way others of his time would discuss Mozart or Beethoven.

Parsons recognized the possibilities of the marine turbine as an economic means of propulsion early on. Turbines were more efficient, had greater power, were faster, weighed less, had less vibration and cost less. In short, an ideal device for powering the ships of the cost conscious shipowners.

Like most visionaries, Parsons' claims for his invention fell on deaf ears. When he was unable to drum up support in the steamship industry or from the military, Parsons decided to build his own ship. The S. S. Turbinia was launched in 1894. Built for demonstration purposes only, the Turbinia was a little over 100 feet long and only 9 feet wide, with a displacement of 44 tons. After experimenting with seven different engine designs, Parsons decided to link three turbines to reuse the same steam in succession. This "triple expansion" system developed 2,100 horsepower, driving three propeller shafts with triple bladed propellers mounted on each shaft. After much experimentation, Parsons worked the speed of the little ship up to 34 knots.

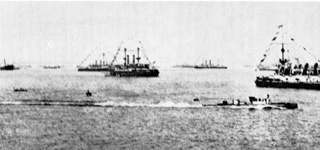

In June, 1897, Parsons found an opportunity to demonstrate the Turbinia's capabilities. At Spithead, Queen Victoria would review the Royal Navy in honor of her 60th year on the throne. Along with the Queen was the Prince of Wales and Prince Henry of Prussia, the Kaiser's brother. Charles Parsons had once written, "If you believe in a principle, never damage it with a poor impression. You must go all the way." Just as the review began, as Prince Edward appeared, and the bands struck up the national anthem, Turbinia dashed out from her position and into the passing review. The picket boat dispatched by the Navy to intercept the intruder was nearly sunk by Turbinia's wash. Before any further disciplinary action could be taken, however, Prince Henry of Prussia sent Parsons his congratulations and asked for a return. Turbinia had triumphed!

As Parsons envisioned, this stunt sparked interest in the use of turbines for marine propulsion. In 1905, the first turbine-powered liners destined for the North Atlantic line were built. They were the 540-foot, 12,000-ton Virginian and Victorian, sister ships for the Allan Line. Cunard followed, powering the Mauretania, Lusitania, and Aquitania using Parsons turbines. In 1906, the HMS Dreadnought was launched. The success of this huge armored warship convinced the Admiralty that turbines were the way to go. Within 12 years, all first line ships in the Royal Navy were turbine-powered.

An amazing career that changed the course of marine propulsion came to a close on February 11, 1931. On that day, Sir Charles Algernon Parsons died at dusk in his bunk aboard the Duchess of Richmond. Anchored in Kingston Harbor, Jamaica, the only thing missing was the sound of an engine.